Max Liebermann and Adolph Menzel shared a complex and long acquaintanceship, which was characterized by a deep mutual appreciation of the other ones craftmanship and challenged by different notions on developments within the perceptions on art.

|

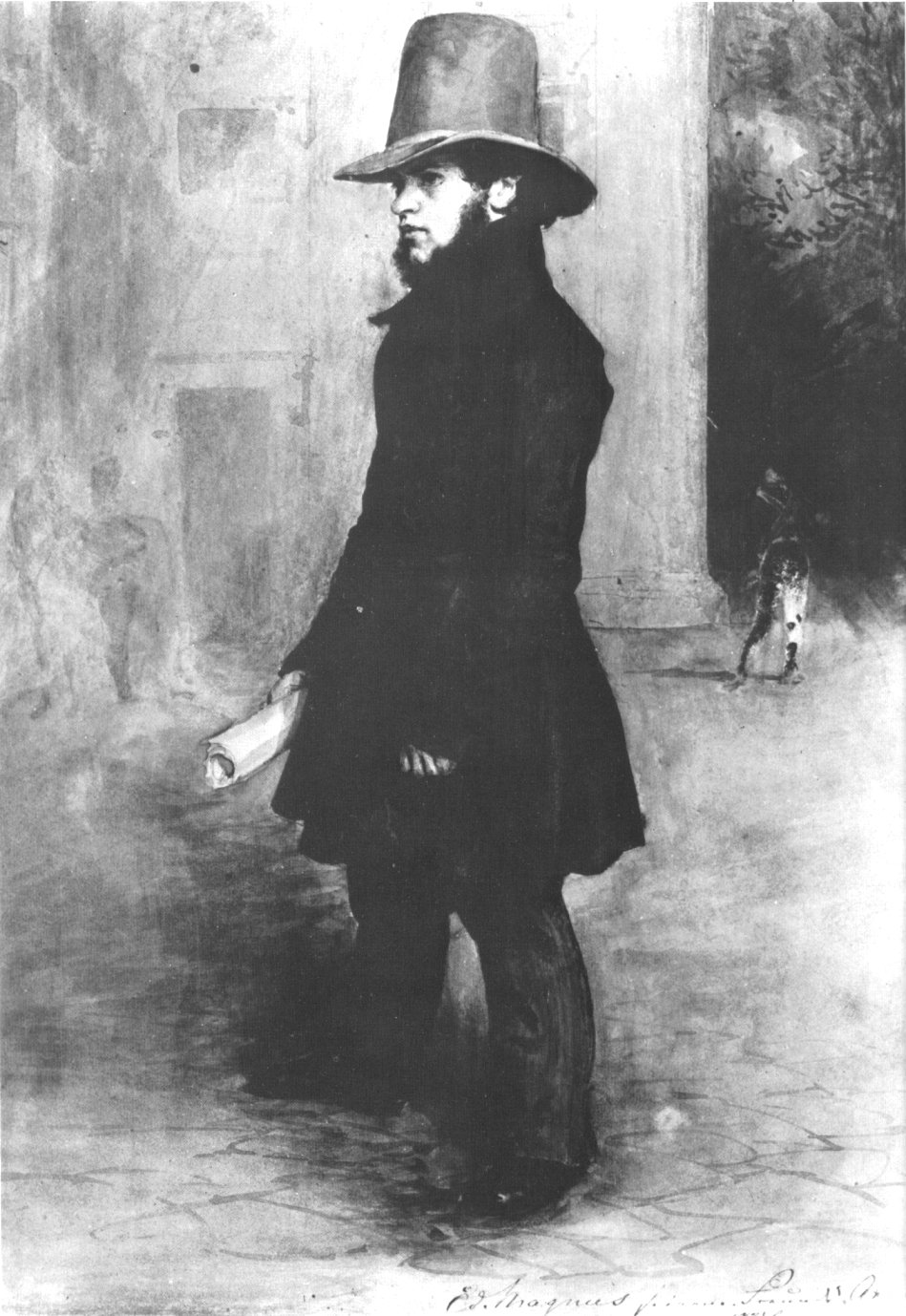

| Max Liebermann, source: Wikipedia |

Liebermann, as the later head of the Berlin secession and one of the most influential German impressionists, describes Menzel's painting process and the importance of his drawings in one of his essays on Menzel. Here are some exerpts:

(...)

In the year 1872 Menzel had seen my

painting „Die Gänserupferinnen“ (the geesepluckers) at the art

merchant Lepke and he let me be summoned, if I, who studied at that

time at the school for fine arts in Weimar would come to Berlin had

to visit him. Without his request I would have never dared to do so

since visiting him in his studio was seen as a daredevilry, equal to

entering a lion's cage.

He welcomed me with the words: „Your

Talent might be given to you by God, I admire only the artist's

diligence!“ which I thought was ment as a fatherly admonishment of

the master towards the apprentice. (…)

| ||

| Max Liebermann, "Die Gänserupferinnen", 1872, source: Google Arts Project |

The peculiar thing about Menzel was,

that the diligence of the genius didn't count for him, but the

eagerness of the clockmaker, the mechanical work. He wanted to owe

everything to himself alone: the work of art shouldn't step into

being under his hand, it should literally be made with his hands.

I believe that no other artist's

procédé was so headstrong as Menzel's. I witnessed as well the

beginnings of the Iron Rolling Mill as of the Piazza d'Erbe: one

horizontal line on the blank canvas indicated the horizon, then one

could see vertical lines, drawn with blue or red chalk, which showed

the sizes of the several figures in their very spot, and while for

example in the rolling mill the wheelwork in the background, on the

Piazza d'Erbe the row of houses and the air were completed and have

never been touched again, the space that was ment for the figures in

the foreground was painstakingly left open.

The painting was completed as soon as

the canvas was covered all over with paint.

|

| Adolph von Menzel, "Das Eisenwalzwerk", 1875, source: Google Arts Project |

This astoundingly selfconfident way of

painting, that he put himself through, becomes even more stunning, if

one knows that since his unfinished painting of Frederic II's speech

to his generals in Leuthen he never used any Cartoon, sketch or any

other preliminary work for his painting than his single drawings. He

didn't paint into a painting after nature but only with help of his

drawn studies, that he stuck to slavishly. I witnessed how he

scratched down the two to three centimeter tall portrait of an old

woman down to the canvas for six times on the Piazza d'Erbe and

repainted it one time after the other, since it didn't show enough

„likeness“ with the portrait on his drawing. (…)

|

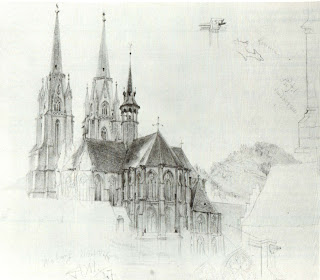

| Adolph von Menzel, study for the iron rolling mill, carpenter's pencil on paper |

Menzel's eminently correct instinct for

the craftmanship within fine art led him to paint alla prima,

opposite to the leading perception; this way of painting, which has

been and will be used by all real masterpainters, old and new, and

which has the advantage, next to the fact that it is the optimal

technique for the usage of oils, consists in the fact that it comes

closest to the realisation of the artist's vision by lending the

sudden impulse, the immediate sensation the most adequate expression.

|

| Adolph Menzel, "Piazza d'Erbe in Verona", 1884, source: Google Arts Project |

But especially this biggest advantage

of painting alla prima was lost again under Menzel's hand because

instead of painting freely from memory – his memory was so strong

that he could, if he forgot somebody's name during a conversation,

draw the very person, to find out about who it was -

or to paint again directly from nature

into the painting he strictly stuck to his drawn studies: the

paintings are thus „only“ a translation of his drawings into

oils, and because of that much weaker than those. Even if he was able

with his gigantic skills and knowledge was able to transfer his

drawings onto the canvas, he couldn't give what characterizes their

beauty and why no copy can reach the quality of the original: the

inspiration, which led his hand while drawing.

Where Menzel paints alla prima from

nature or from memory – which is basically the same – he creates

virtually something immortal.

|

| Adolph von Menzel, study for "Piazza d'Erbe in Verona", carpenters pencil on paper |

As proof: the countles pastells,

gouaches, the Balcony room and the other interiors from his

appartment in Ritterstrasse, the „Laying out of the fallen of the

revolution of march“, the Gardens of prince Albrecht (…). All of

those works, which originated casually, as recovery from the efforts

from working on the big paintings and which have been appreciated by

Menzel himself little if at all, are unsurpassable masterpieces. (…) They are timeless.

|

| Adolph von Menzel's bedroom in his studio in Ritterstrasse |

(...)

I skip here the many probably known

anecdotes, that are circulating about his „franckness“, if it is

not to be called crudeness, and I only want to mention one incident

that might only be known to me, to demonstrate that he even remained

his independence face to face with someone like Bismarck.

Menzel had entrusted me with 16 or 18

of his pieces, since I was appointed by the french government as

juror of the admssionary panel for the world exhibition in Paris in

1889, when all of sudden a decree by Bismarck was published which

prohibited all artists who were prussian officials to participate.

And all of those former celebrities like Achenbach, Reinhold Begas,

down to the uprising newer stars, hurried to take back their works.

Except Menzel; even as a ministerial director showed up to explain to

him that for him as the chancelor of the order pour le merité, it

wouldn't be appropriate to participate in an exhibition in Paris that

celebrates the centenary of the french revolution. Menzel replied: I

am now 73 years old, I always knew what was respectable for me and I

will also know it in future times.

Spoke like that and exhibited without a

worry.

Dostojewski writes in one of his

novels: There is no sadder time, then when we don't know whom to

adore. Let's be glad, in theses sad times to have a man in Menzel,

who we can adore as an artist as well as a human being.

The whole essay of Liebermann in german language can be read in

Adolph von Menzel, "Das graphische Werk"

More prestudies for Menzel's paintings are also included in

Drawings and Paintings by Adolph Menzel on which I had the honour to work as coeditor together with James Gurney.

Wikipedia article on Max Liebermann

and on Adolph von Menzel